Open Educational Resources and California Community Colleges

At the League's Annual Trustee Conference in late April of this year, Dr. Cable Green, Director of Global Learning at Creative Commons, gave a presentation on Open Educational Resources (OER) that stirred considerable interest among attendees with OER’s potential to save students substantial money while continuing to provide a quality educational experience. The interest among participating trustees inspired the League to investigate the state of OER in California with a particular focus on legislation and activity relevant to our 113 community colleges. Therefore, the goal of this article is to provide California community college leaders a snapshot of the universe of OER legislation and related activity as of June 2016.

A review of the activity surrounding Open Educational Resources demonstrates that the issues surrounding potential mass use of OER are many, yet a combination of pragmatic legislation, diligent and relevant work by the California Open Educational Resources Council (COERC), and student demand for increased access to affordable higher education, leads me to believe that substantially increased use of OER by faculty and their students in California community colleges is forthcoming. Still, although too slowly for some, this shift will likely take place over many years requiring considerable effort from all higher education segments, including necessary financial and human resources.

What are Open Educational Resources (OER)?

Creative Commons (Website) defines Open Educational Resources, or OER, as freely and openly licensed educational materials that can be used for teaching, learning, research and other purposes. The WikiEducator OER Handbook (Website) further includes OER as educational resources (lesson plans, quizzes, syllabi, instructional modules, simulations, etc.) that are freely available for use, reuse, adaptation, and sharing.

Economics 101

Apart from publishers, their stockholders, and successful authors, it is difficult to identify defenders of the status quo when it comes to college textbooks. Whether you label it “market failure” or monopoly capitalism, according to one report, five large textbook publishers control 90 percent of the $8.8 billion market (Allen, N. 2013). A University Business article places the value of the industry closer to $15 billion (Opidee, 2014). And since there is not a direct producer-to-consumer market for textbooks as there is for most other products, publishers largely have a captive market, and students are subject to faculty choices surrounding instructional material. A General Accounting Office (GAO) study explains that textbook costs have increased 82 percent in the last decade; and a 2014 report by Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGS) found that since 1978 textbook prices have increased 812 percent or 3.2 times more than the rate of inflation (Senack, 2014). The same study reveals that 65 percent of students surveyed skipped purchasing or renting a textbook for a course in which they were enrolled because it was perceived as too costly. Ninety-four percent of those same students believed that foregoing the textbook would likely affect their grade in the course. As stated in the U.S. PIRG Study, “…Students are not only choosing not to purchase the materials they are assigned by their professor, but they are knowingly accepting the risk of a lower grade to avoid paying for the textbook” (Senack, 2014). And with time-to-degree and degree-completion nationwide imperatives, almost half of 2,039 students from more than 150 institutions of higher education surveyed declared that textbook cost had affected the number of courses they chose to take each term.

While growing numbers of faculty employ a variety of means to keep the costs for students as low as possible with textbooks on reserve in the library, using classroom packets rather than textbooks, and some adopting Open Educational Resources, the majority of higher education faculty continue to use traditional textbooks with considerable price tags.

What is Happening in California to Address this Critical Access, Affordability and Student Success Issue?

Below is a chronicle of major legislation and related efforts seeking to address the cost of college textbooks by encouraging the adoption of Open Educational Resources including digital textbooks.

- 2008: Joint Legislative Audit Committee requests State Auditor report on the affordability of college textbooks.

- 2012: Senate Bill 1052, Steinberg (EC §66408) establishes the California Open Educational Resources Council (COERC) to develop or acquire high-quality, affordable, digital open source textbooks for 50 high-enrollment, lower-division courses common across the three segments of higher education. (Legislative Analyst Office "The 2016-17 Budget: Assessing the Governor's Zero-Textbook-Cost Proposal," Mac Taylor, March 14, 2016.)

- 2012: Senate Bill 1053, Steinberg (EC §66409) establishes the California Digital Open Source Library (currently known as COOL4Ed) to house materials identified by the California OER Council and make them available over the Internet for students, faculty, and staff to easily locate, use, and modify. Statute requires that materials in the library include a Creative Commons license that permits the public use, distribution, and creation of derivative works, with attribution to the authors. (Taylor, LAO).

- 2012: Senate Bill 1028, Committee of Budget and Fiscal Review appropriates $5 million to support the COERC, COOL4Ed, and OER acquisition process, contingent on securing a dollar-for-dollar private match. A portion of this funding used for a competitive proposal process for faculty to produce 50 courses using OER required by SB 1051 (EC §66408).

- 2013: The CSU awarded grants by the William and Flora Hewitt and Gates Foundations, thus fulfilling the requirement of SB 1028.

- 2015: Assembly Bill 798, Bonilla, created the Open Educational Resources Adoption Incentive Fund providing up to 100 grants of up to $50,000 for campus, staff, and faculty efforts to expand the use of OER at CCC and CSU. The COERC issued a request for proposals for AB 798 grants in February 2016, with a June 30, 2016 deadline (Taylor, LAO, Navarette, League).

- 2015: COERC identified more than 160 digital textbooks for the 50 high-enrollment lower-division courses required by legislation.

- 2016: Governor Brown proposes $5 million in one-time funds for the creation of "Zero-Textbook-Cost Degrees" at the California Community Colleges. Zero-textbook-cost degrees permit students to complete a degree entirely by taking courses that use only no cost OER.

Useful Sources for Information on OER for California Community College Leaders

An excellent resource for understanding the status of OER in California community colleges is the Community College Consortium for Open Educational Resources (CCCOER) (Website). The CCCOER seeks to develop awareness and assist colleges in creating and/or repurposing OER. The CCCOER is a joint effort by individual community colleges, regional and statewide consortia, the open courseware consortium, the American Association of Community Colleges, the League for Innovation in the Community College, and others seeking to facilitate development and use of OER.

The California OER Resources Council (COERC) emerged in 2012 from Senate Bills 1052 and 1053 directing the three public higher education sectors to create an online library with OER and digital textbooks with the goal of increasing faculty adoption of affordable or free quality educational materials. The collaboration among the UC, CSU, and CCC faculty occurs under the scope of the COERC. The intersegmental council facilitates review of digital textbooks for inclusion in the California Open Source Digital Library (Website).

In the COERC's very informative White Paper, OER Adoption Study: Using Open Educational Resources in the College Classroom, the Council concludes that outreach and increased knowledge of OER will inevitably lead to greater participation. In other words, although there are very real and important issues and even barriers to faculty adoption of digital textbooks and other OER, such hindrances are less significant than the lack of familiarity with the existence of OER already available for use.

To quote from the conclusion of the COERC White Paper, "OER in general still suffers from a lack of extensive outreach and education. Rather than OER textbooks and materials needing further infrastructure, education about existing OER resources and materials needs to be widely distributed across colleges and universities." (View White Paper)

Barriers to OER Use Cited by Faculty Participating in the Research by the COERC (which included both surveys and focus groups)

Adequate time to identify quality digital textbooks, considering either their lack of perceived quality and/or their inconsistency, is considered a key barrier. Additionally, whereas the major publishing companies send representatives to campuses to promote traditional textbooks complete with a variety of supplementary materials, digital textbooks generally lack both such promotion as well as ready-made PowerPoint slides and/or TestBanks. Hence, faculty adopting digital textbooks also require time to create their own supplementary materials.

Another concern and barrier to OER adoption is the absence of a gatekeeper monitoring the quality, relevancy, and credibility of the material. As is the case with Wikipedia, for example, concern remains that OER do not have the infrastructure of a publisher and research capacity to consistently monitor and maintain quality and authority of the material to academic standards.

Faculty remain concerned about student access to the internet and the technology to access OER. Although many students do have cellphones and/or computers available for off-campus use, the interface may not always be ideal nor available continuously for some students. Even for students with cellphones, some of the OER material may not be as visually compelling or even decipherable via certain platforms. The digital divide and technological issues remain pertinent for OER adoption and use.

Faculty in the COERC survey also reported concerns and even inaccurate information about copyright. Not all faculty are familiar with, for example, the Creative Commons licensing options (link) which include a variety of different layers of public use and reuse.

Additionally, faculty spoke to department, institutional, and even discipline acceptance or "buy-in" of OER. Does the department or institution provide technological and other support such as instructional design to faculty adopting OER? Would CSU and/or UC accept credit from faculty employing OER in their courses? Do academic disciplinary peers perceive OER as credible?

The faculty in the pilot study identifying the quality of the digital textbook as superior and/or equal to a traditional textbook far outnumbered those viewing it as inferior. Although support for student learning with OER and ease of use were cited by faculty, the paucity or poor quality of supplementary materials was viewed as a disadvantage of digital textbooks. Still, faculty viewed OER as means to reflect upon their course design and pedagogy. It should be noted that for the most vocal champions of the OER movement, reconceptualization of the entire teaching and learning process is cited as one of the most important outcomes of a move to OER.

For example, Quill West, the open education project manager at Pierce College District in Washington State, remarks, “…[O]pen education is also about increasing student achievement, inspiring passion among faculty, and building better connections between students and the materials that they use to meet their educational goals” (Jensen and West, April 2015).

Of the 351 students surveyed about their experience with OER, the most oft-cited challenge concerned poor or lack of internet connection. Screen fatigue and searching the text were also identified by students as challenges with digital textbooks. Other perceived disadvantages were font size, download speed, and file size, among others. Nevertheless, despite the aforementioned problems with digital textbooks, faculty and students in the COERC pilot studies identified several advantages of OER.

A slight majority of the students in the pilot project found the digital textbook to be equivalent to that of a traditional text, while those viewing it as superior far outnumbered those perceiving the digital textbook as inferior. In their comments, students cited the convenience and low cost as powerful advantages of digital textbooks.

Policy Issues

At the statewide level, it is evident that state legislators will continue to advocate for OER as concerns about the escalating cost of higher education and textbooks continue apace. A superficial understanding of the multifaceted issues concerning the transition to digital textbooks and OER in general require vigilance by everyone concerned with quality higher education in California. Just as "free tuition" is not as simple as it sounds, Open Educational Resources and "free online textbooks" are equally compelling to lawmakers, their constituents, and financially-strapped, internet savvy students. Informed trustees and CEOs will play a key role in advocating for a thoughtful approach to policy issues surrounding the OER ecosystem. In addition to educating and informing policymakers and stakeholders throughout the 72 California community college districts, maintaining faculty leadership and student involvement in this work is necessary for its advancement.

Statewide, and/or district and institutional professional development and support must be an element of the overall equation. Both nationally and within California, financial and temporal support for faculty, instructional design, and information technology professionals on campus have proven important in successful adoption of OER. As cited in the CEORC White Paper, OER implementation at Penn State and the University of Colorado (see White Paper) benefitted from adequate professional development and support.

Based on review of the literature and experiences in other states, as well as the current state of OER in California, institutional leadership focused on managing expectations of overly enthusiastic policymakers and student leaders, while simultaneously encouraging and supporting OER at the district and campus level will likely result in increased use of quality OER and save students substantial money over the course of their higher education experience.

Board Member Spotlight

CEOCCC Board Member Dr. Jose Fierro

When I asked Dr. Jose Fierro - who was appointed President/Superintendent of Cerritos College in July, 2015 - about how he maintains balance while working relentlessly to increase student degree-completion and supporting a commitment to access, he responded in his familiar poised manner that he squeezes in workouts consisting of running, swimming, and/or cycling five to six days weekly. “It gives me time to process and think.” While most busy professionals appear harried and over-caffeinated when describing a regime of 60 plus-hour workweeks and ambitious and consistent exercise regimes, Dr. Fierro describes his intense schedule in the same easygoing manner to which his CEO Board colleagues have become accustomed. Unquestionably, his ambitious goals for the college, internal and external responsibilities as Superintendent/President, and statewide work as Area 7 representative on the CEO Board, necessitate considerable creativity in identifying time to workout.

When I asked Dr. Jose Fierro - who was appointed President/Superintendent of Cerritos College in July, 2015 - about how he maintains balance while working relentlessly to increase student degree-completion and supporting a commitment to access, he responded in his familiar poised manner that he squeezes in workouts consisting of running, swimming, and/or cycling five to six days weekly. “It gives me time to process and think.” While most busy professionals appear harried and over-caffeinated when describing a regime of 60 plus-hour workweeks and ambitious and consistent exercise regimes, Dr. Fierro describes his intense schedule in the same easygoing manner to which his CEO Board colleagues have become accustomed. Unquestionably, his ambitious goals for the college, internal and external responsibilities as Superintendent/President, and statewide work as Area 7 representative on the CEO Board, necessitate considerable creativity in identifying time to workout.

Prior to his presidency at Cerritos, Dr. Fierro served as the Vice President of Academic Affairs and Chief Academic Officer at Laramie County Community College. And before he made the geographical and cultural switch from Wyoming to California, Jose was Academic Dean, Associate Dean of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and professor of biological sciences at Florida State College.

Dr. Fierro’s leadership at Cerritos College affords him the opportunity to work with colleagues on initiatives aimed at supporting student access and success. Two prominent efforts include Cerritos Complete – a Promise Program in collaboration with area high schools; as well as offering students a burgeoning list of textbook-free courses taught by faculty utilizing open educational resources. As the name indicates, Cerritos Complete aims for degree attainment. Dr. Fierro describes the initiative as a collaboration with the five area high schools offering one year of tuition-free attendance for seniors agreeing to sign a contract with Cerritos College and participation in evidence-based preparation, advising, and pathways practices during their educational experience at the college. At this early stage, some 800 students are already set to take advantage of the Program.

Another leadership initiative championed by Dr. Fierro focuses on offering students an increasing number of courses eschewing expensive textbooks for open educational resources (OER). Some 150 courses at Cerritos employ OER, and Dr. Fierro believes that by 2017 Cerritos Faculty will offer as many as seven entire programs solely employing OER.

Asked about his willingness to serve in a statewide role on the CEO Board, Dr. Fierro views his service as an opportunity to enhance his involvement in the larger California Community College System, a means to accelerate his understanding of the myriad statewide issues, and as an opportunity to build a personal and professional network of colleagues confronting many of the same challenges and opportunities as a college leader.

While there remains significant concern about the so-called "leadership crisis" in community colleges with so many experienced presidents retiring, spending time with Dr. Fierro is a reminder there is considerable young talent leading institutions in California’s most dynamic sector of higher education.

Dr. Fierro is dedicated to his role at Cerritos College, but he’s also a devoted husband. In his free time, Dr. Fierro explained that he often tries to have his spouse, Melanie, attend college-related events, celebrations, and cultural activities, since they are both busy professionals.

CCCT Board Member Linda Wah

Pasadena City College and California Community College Trustee (CCCT) Board member Linda Wah exemplifies what's best about the unique cultural dynamism and important civic, economic, and broad educational mission of our community colleges.

Pasadena City College and California Community College Trustee (CCCT) Board member Linda Wah exemplifies what's best about the unique cultural dynamism and important civic, economic, and broad educational mission of our community colleges.

In reflecting on her pioneering and successful career, as well as her important civic and political engagement, Trustee Wah points to her return to higher education at a community college a decade after having children as instrumental in entering the technology sector via an internship program at the community college.

In the mid-70's there were few Asian-American women in the technology sector, yet this did not deter Wah from pursuing an internship that ultimately led to a very successful career in management in technology. And as Trustee Wah points out, not only was she a returning college student with a family, but she had participated in concurrent enrollment, and attended college part-time, hence her clear understanding of many of the challenges faced by our sector's students.

Ask just about anyone active in California's Asian-Pacific Islander (API) Community about Linda Wah and they will recognize her as one of its leading voices. Wah was the first API Trustee elected to the Pasadena City College Board. And just before this article was written, she was the top vote-getter to earn a spot as a delegate for the national Democratic Party Convention in Philadelphia representing Congressional District 27, which is now a majority-minority API district. As a long-time champion for women’s issues and affirmative action, there is a certain poetic justice to Trustee Wah’s trailblazing electoral success as a delegate to the political convention that is likely to nominate the first woman in US history to be a major political party’s nominee for president.

As a trustee at Pasadena City College and serving on the CCCT Board, Wah has been a leader on K-12/community college articulation work, including service as president and program chair of the Los Angeles County School Trustee’s Association. In addition, Trustee Wah was a leader of the Strong Workforce Task Force as a CCCT representative.

When she’s not busily engaged in the aforementioned educational, civic, political and cultural work, Linda enjoys mountain bike riding, kayaking, and even shares an interest in sewing and knitting with her CCCT colleague Ann Ransford from Glendale Community College.

Recommended Reading

Is the prevailing vision for community colleges - one of access and especially completion - that emerged from the 2007 global financial crisis, the best that we can imagine?

Is the prevailing vision for community colleges - one of access and especially completion - that emerged from the 2007 global financial crisis, the best that we can imagine?

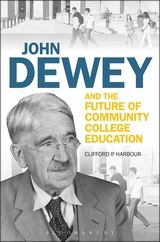

Such is the animating question at the heart of Dr. Clifford P. Harbour's engaging book John Dewey and the Future of Community College Education published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Press. Harbour is Associate Professor in the College of Education at the University of Wyoming, President of the Council for the Study of Community Colleges, and served 14 years as a faculty member and administrator in the community college sector.

While summer is often the time for fiction and those national and international book prize winners you haven't had time to read during the academic year, I would highly recommend Dr. Harbour's text for a well-written and researched, relevant, and thought-provoking book that challenges the current zeitgeist and national discourse concerning the purpose and functions of community colleges.

Harbour makes a compelling case that the current economic logic now framing many public higher education issues - and the community college Completion Agenda that is ascendant - is not merely insufficient but a threat to the current and future well-being of these vital institutions of higher education. Instead, the author argues for a 21st century normative vision for community colleges that includes a much more student and community focused approach; one that helps adult learners grow not simply vocationally, but as members of their respective communities; and one that posits that community colleges need to take a stronger leadership role in developing democratic communities by doing what they do best: helping solve community problems through education (Harbour, p. 28).

To accomplish this, the author reintroduces the reader to 20th century philosopher John Dewey's writings on the interdependence of democracy and education. Special attention is paid to Dewey's belief that central functions of education include helping individuals better understand the problems facing their communities, and developing the capacity to collaborate with others to identify solutions and to achieve personal and intellectual growth.

In the hands of a lesser author, the book could be pedantic or utopian. However, Harbour's historically-grounded extended argument, as well as his extensive research and understanding of the works of John Dewey focused on education and democracy, make it more of an edifying lecture by one's favorite professor rather than an angry screed which has become all-too-familiar in today's mainstream public discourse.

Harbour begins with the development of community colleges from their institutional predecessor the junior college, and describes how they acquired the traditional vision of expanding educational opportunity. Notably, his research and synoptic history of the development of the community college counters the mainstream narrative and conventional history of the sector as one becoming more and more organically responsive to the educational needs of the local community. Habour's more expansive historical perspective provides the foundation to understand how an institution committed to educational opportunity could so quickly shift to one aligning with national economic policy. And it is here where readers without a critical perspective and familiarity with Neoliberalism will benefit from its mention. Although the book does not delve into great detail about this globally omnipresent ideology and practice, and how it affects public institutions such as community colleges, if its mention spurs reader's interests to investigate Neoliberalism the book will have served at least one important purpose. Harbour then argues how the Completion Agenda threatens the traditional animating vision of educational opportunity. The author then introduces the reader to relevant writings and speeches of American Philosopher John Dewey and how his perspectives on education and its relationship to democracy represent a new normative vision for community colleges to better serve students and their communities. Harbour grants that promoting completion at community colleges is necessary, however throughout the text makes a strong case that "Democracy's College" (as community colleges have been called), will better serve students with what he refers to as a "Deweyan normative vision" which foregrounds students' individual growth and the development of democratic communities. The latter part of the book identifies and explains the values and priorities comprising this new normative vision animated by the work of John Dewey.

John Dewey and the Future of Community College Education is an important book for anyone interested in better understanding not only the historical development of this sector of higher education serving upwards of 40 percent of the undergraduates in the US, but the political and economic forces buffeting "Democracy's Colleges" and threatening their expansive and historically significant roles in facilitating individual growth and strengthening democratic community building.

Clifford P. Harbour is Associate Professor in the College of Education at the University of Wyoming, USA, and President of the Council for the Study of Community Colleges, USA. He was a community college faculty member and administrator for 14 years. More Information

Dr. Harbour will be a Keynote Speaker at the League's 2016 Convention in Riverside. For more information about Convention, click here.